The most basic assumption about riding a horse is to go, to move. But there is more to it: The horse needs to learn to move from a cue, and remain moving in a steady fashion of his own volition, in the gait and tempo we dictate, like a car in cruise control, until we tell him otherwise.

To initially set a horse in motion, or move from the halt to the walk, most horses will spontaneously “go” as a result of a slight squeezing of both legs. Leg aids work because they touch and activate the horse’s abdominal muscles, which pull the hind legs forward and lift the back.

You want to teach your horse to respond to subtle aids from the outset—quiet signals from the seat, weight, legs, hands, and voice. These are the “natural” aids that communicate with the horse. Whips and spurs are “artificial” aids that should only supplement or refine natural aids.

Illustration by Taylor Sterry

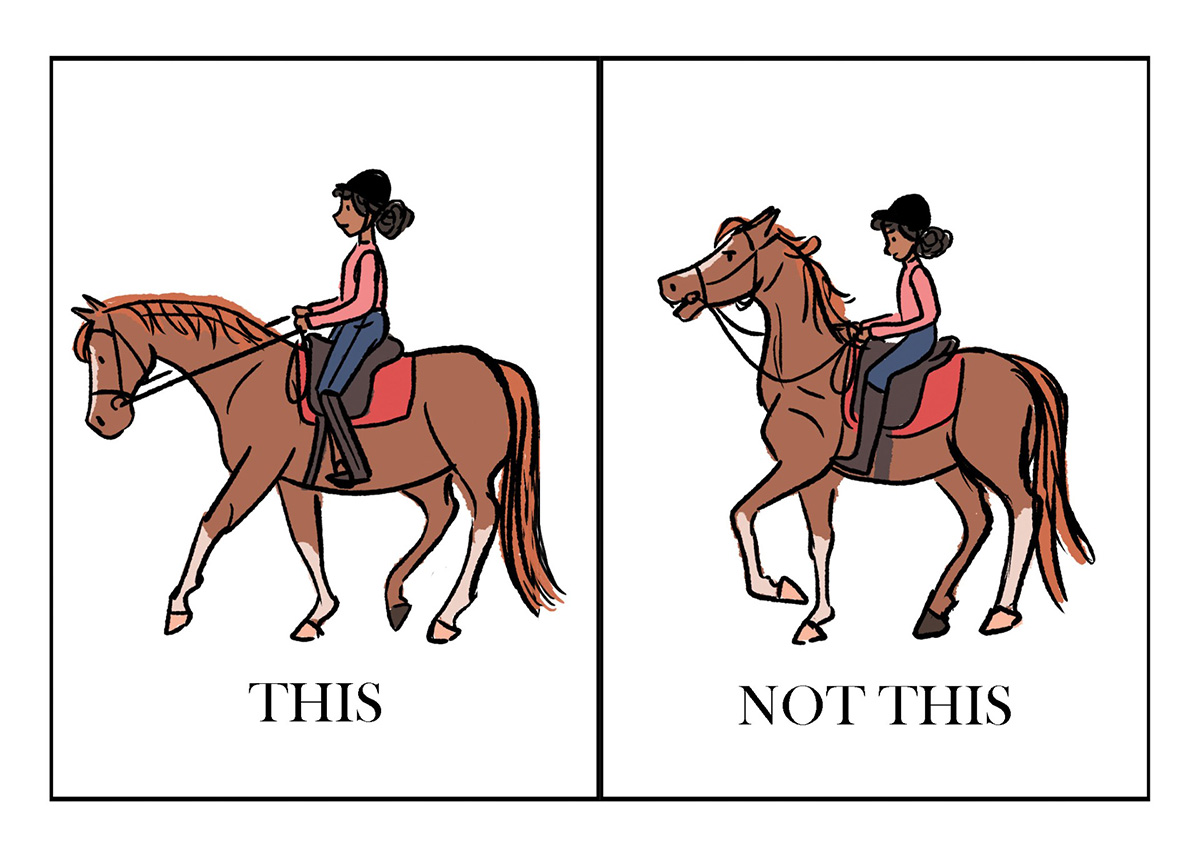

It isn’t necessary to use sharp kicks as are so commonly employed. You don’t want to teach your horse that harsh or repeated aids, like pumping your seat or kicking, are the cue to go, or you will become tired and frustrated from doing that the rest of your riding life. Indeed, you will likely end up escalating your kicking or pumping as time goes by because your horse may wait to see whether you are finished, or when you finally give that last “hard enough” kick or push. In fact, pumping with your seat actually produces the opposite effect of what you want: the pressure causes the horse’s back to sink, his head to rise, his croup to rise, his front legs move out in front of him and his hind legs move out behind him, so that he becomes shaped like a trapezoid. His lowered back and belly actually prevent his hind legs from moving forward.

Aids Inform the Horse—They Are Not the Moving Force

Consider riding aids to be a form of sign language in which gestures convey meaning; a specific bodily movement means “go.” Such a signal informs the horse to go; the application of the aid itself does not physically compel the body to move. When a horse understands, he will go.

Because your horse only knows what you teach him, be judicious and show him what he is meant to do when you communicate with him through the use of an aid. Use specific and consistent aids for each response you seek. Apply a gentle aid and see whether you get the desired response. If not, be more aggressive for one try then return to the slight aid. Often, horses offer several simultaneous responses when given an aid, so eliminate everything but the response you want. Eventually, your horse will understand that that request is the one and only aid for one action—“one response for one aid.”

As riding instructor Sharon Vander Ziel remarks, “People always say that a horse can feel a fly landing on him, but did you ever notice that horses ignore flies? They’ll ignore you, too!” This shrewd observation reminds us that everything doesn’t work perfectly or instantly with horses, so be patient, keep trying, and expect results in small increments. Ask gently. If you don’t get a response, ask bigger until you do, then return to the slight aid.

Be Consistent

Many people don’t realize they routinely use random aids. For example, many who want to trot urge their horse forward, pumping and kicking, without thinking it through. When I ask students to tell me what they systematically did to ask their horse to trot, they often just stare at me, perplexed. Such inconsistency creates confusion in the horse and puts him in the position of having to guess what you are asking for. When he guesses wrong, he may be blamed for being disobedient.

Be methodical and patient with giving only the cue that you want to use until you get the response that you seek. Remember that alphabet that dressage trainer Jane Savoie taught us: Think of giving aids like spelling a word—if you want your horse to trot, make sure you spell “t-r-o-t” the same way every time; don’t spell “k-i-w-i” one time, then spell “c-l-o-w-n” yet another. Giving aids in different combinations, or “spelling different words,” compels your horse to guess what you want, and aids should not be unanswerable multiple choice situations.

Illustration by Taylor Sterry

The minute you turn the corner and decide to be 100 percent clear, precise, and consistent with your horse on everything, you’ll find your horse will better respond to your requests. It can help to think of the kata in martial arts: a kata refers to a prescribed, detailed pattern of specific, choreographed movements that are repeated under the eye of a master until the movements being executed are perfected. Experts say the purpose of kata is to train the muscles. By consistently doing the same motions, your brain will become more comfortable with lacing together combinations and turning and moving a certain way. Eventually, you will be able to habitually duplicate particular movements without conscious effort; it becomes “first nature”—something you “are” rather than something you “do.” If you bring the kata mentality to using your aids, your horse will never be confused about what you are telling him. It will be kata for him, too. The more deliberate you are, the happier you will be in the long run because you will have effectively installed the cue that you want to use.

This excerpt from How to Ride the Horse You Thought You Bought by Anne Buchanan is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.