For successful saddle fitting, it is as important to address the dynamic stability of the rider as it is the horse. A horse should be able to perform at his best without discomfort. The same is true for a rider.

Some elements make it more challenging when evaluating a rider’s fit in the saddle in any English discipline, whether it is dressage, jumping, trail riding, or another activity. The following are just a few tricky issues that saddle fitters run across:

◆ There is often a mismatch between a rider’s perception and reality because human cognitive sensory information relies on patterns. As an example, if a rider regularly sits to the right side of the horse whenever mounted, the brain believes this position is correct and straight. In brief, the rider’s perception of her position and actions in the saddle is frequently inaccurate! As a result of this perception, when asked what kind of saddle fit a rider “likes,” the rider will usually “like what she knows,” versus “knowing what she likes.” We humans like familiarity, even when it is damaging.

◆ A rider may believe her horse’s lameness or movement issue is due to a problem with the horse, even though the horse doesn’t appear lame until the rider mounts up. Rider-influenced causes tend to go unnoticed, and instead we focus on the horse when we should be addressing the rider’s issues, or a problem with the fit of the equipment used.

Art by Beverly Harrison

◆ Riders, particularly more advanced riders, regularly ride through physical pain. That pain causes distortion of their position and compensatory movement. Rider compensations, often enacted unconsciously, occur to maximize the rider’s own comfort and effectiveness, but they typically affect the movement of the horse in a detrimental way.

◆ There is not much consistency in the education of riders today, particularly in the United States, where a standardized curriculum does not exist. Theories and techniques are mostly up to individual trainers, with little commonality between trainers, and we do not have a precise standardized terminology with which to teach riders.

◆ Amateur riders generally spend most of their time in non-riding activities. Many of those activities undermine the symmetry that is so important to riding. For example, static positions assumed while driving a car or sitting at a computer all day create stiffness and asymmetry in the body, and weakness of the core muscles. It is clear that horses develop a locomotor strategy to compensate for such inconsistency and rigidity in the rider. The outcome of rider asymmetry, such as significantly weighting one stirrup more than the other, pulling on one rein (thus using one seat bone more than the other), or collapsing through one side all causes the saddle to compress more on the weighted side and shift to the weighted side compromising the horse’s spine, and can deform the shape of the panels, as well as cause compensatory movement in the horse.

Art by Beverly Harrison

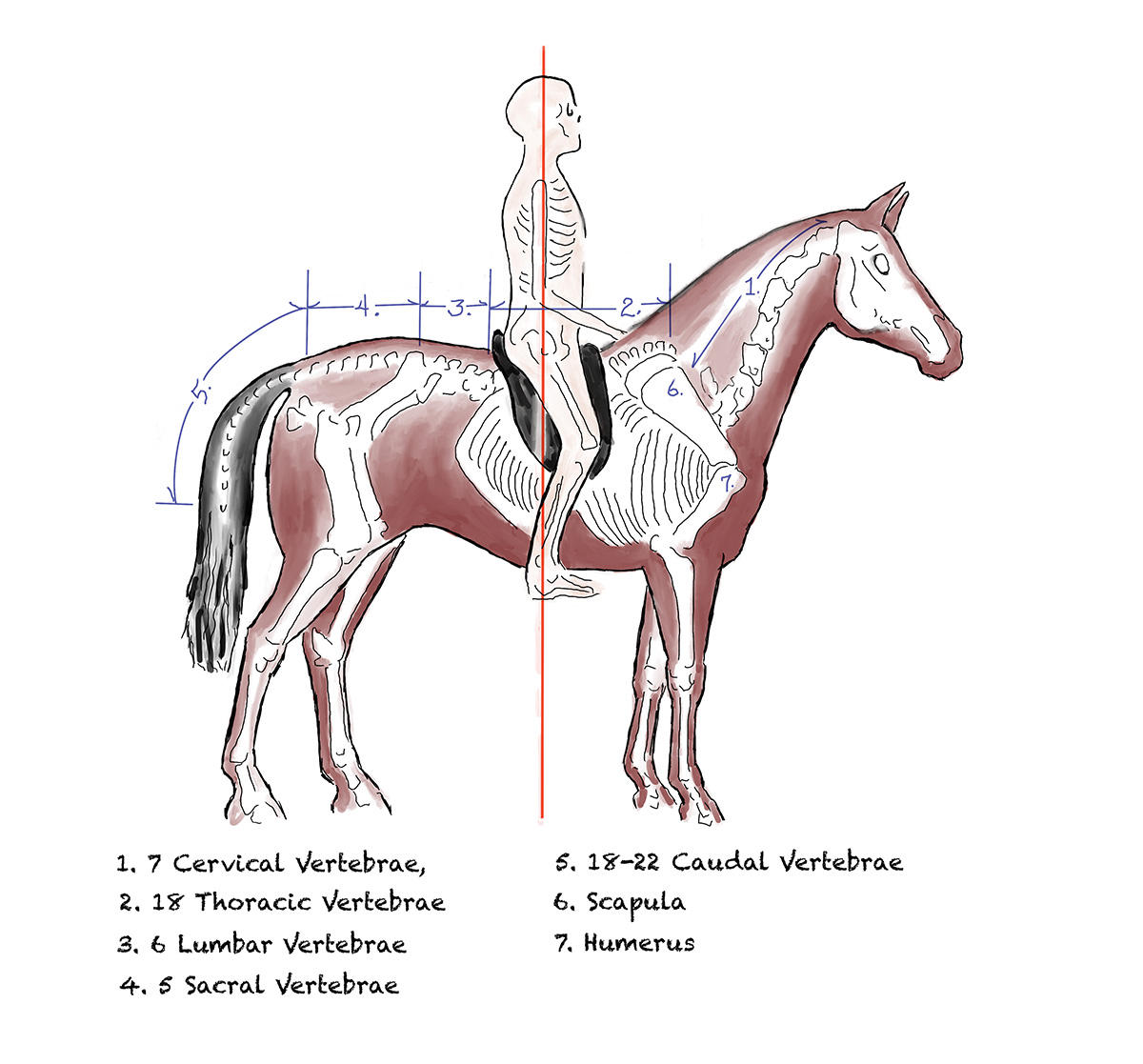

All the rider considerations just listed come into play when addressing saddle fit. Ground reaction force (GRF) from the horse’s hooves contacting the ground come up through his limbs while the pressure of the rider pushes downward on the horse’s back. The saddle sits in the middle. Consider a right-hand-dominant rider—that rider is likely stronger throughout her right side. In response, her horse may then brace through his ribcage on the right side, causing the saddle to collapse and deform on that side, or push sideways and shift more to the left. Either way, the result is crooked.

The amount of pressure from the rider on the horse’s back increases with speed of locomotion:

◆ Walk: Pressure is equal to the weight of the rider.

◆ Trot: Pressure is two to three times the weight of the rider.

◆ Canter: Pressure is three to four times the weight of the rider.

With these numbers in mind, it is clear that at the walk, a crooked rider has less negative impact on a horse’s back than at the trot and canter. Forces from the rider are increased in those faster gaits, as well as when jumping. The more suspension the horse has—the more bounce in the gaits—the greater the pressure from the rider. And it is also increased when the rider is stiff, unbalanced, or uncoordinated.

Art by Beverly Harrison

As equine athleticism increases through selective breeding, effective and balanced riding is much more challenging. It follows that there must be a change in the style of modern saddles to address the needs of the rider. As little as 30 to 40 years ago, jumping, dressage, and English-style trail saddles were essentially flat in the seat with very little, if any, knee roll. Now, saddles tend to have a deeper seat, larger knee rolls, sticky leather, and everything but a seat belt to keep riders more secure. This is particularly influenced by the number of amateur riders entering the market with a healthy budget for saddles with attributes that will help them achieve their goals on expensive, athletic horses.

When the seat of the saddle becomes deeper, with defined spots for the seat bones and knee rolls that control rider leg position, it is very easy to damage the rider if the saddle is not fit correctly—to both her and her horse. Anatomical features of each rider have to be recognized and understood when choosing a new saddle, or when achieving and maintaining balance in an existing saddle.

This excerpt from The Illustrated Guide to Saddle Fitting by Beverly Harrison is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.