With halter in hand, you open the gate to your horse’s paddock. You are in a hurry since the farrier will arrive any minute. Your horse is thinking about running. When you take another step toward him, your hard-to-catch horse turns again—then he’s off. You’ve seen this behavior before and know you’re in for a long session of playing catch.

This hard-to-catch behavior may start as a game or simply as a way for your horse to let you know he’d rather not work. Without a plan to change your horse’s reaction when he sees you approach with the halter, the vice may make you feel annoyed and even defeated.

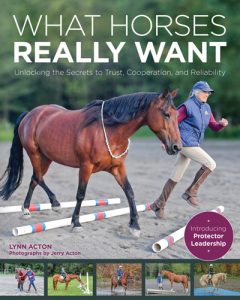

Here, trainer Jessica Dabkowski of Pony Peak Stangmanship in Laporte, Colo., shares her positive reinforcement technique. Dabkowski focuses on natural horsemanship techniques while training Mustangs and all breeds of horses.

For horses that are prone to running away, or don’t want to face you, the following technique can help your horse learn to think rather than react. You’ll teach your hard-to-catch horse that touching the halter—and ultimately putting his nose into the halter—is much more rewarding than running. Dabkowski uses treats to motivate her horses to act out the behaviors she requests.

“You’re shaping your horse’s behavior using food rewards, but your end goal is to not need the food,” says Dabkowski. “One of the great things about using food for training—as long as the training is structured—is that you can help your horse get out of the freeze-fight-flight mode and you can encourage him to seek and think.”

Positive Reinforcement Basics

When you’re using positive reinforcement, you aren’t lavishing treats on your horse for no reason. You are “marking” a behavior that you want to see again as you verbally say “good” and then follow up with a treat.

Choose treats that aren’t full of sugar. Dabkowski suggests breaking up a hay cube, using hay pellets, or looking for natural-based treats. You’ll also need a hip pack to keep treats at the ready.

When it’s time to treat your horse, make sure to give the treat away from your body. The horse only gets a treat when he is in the correct neutral position. If you’re not asking your horse to approach the “target” at the moment, he shouldn’t get a benefit from a treat.

Eventually, you’ll want to be able to put the halter on without needing food. If you say “good,” you’ll create such a strong reinforcement history that your horse will have the same neurological response as when he receives food.

Getting Started

Confine your horse in a small area so that he can’t run across a large field. Remove the lead from a rope halter so you don’t have too much to hold. Walk in to the pen with a calm presence, and resist the urge to walk forward fast. If your horse looks at the halter, say “good” and offer a treat.

Our model horse, Charlie, allowed Dabkowski to be close but tensed when she held up the halter. She held up the halter and said “good” and gave a treat when he simply looked at the halter. Soon, he realized he could get treats and was willing to touch the halter as she held it in one hand.

Work through the following steps slowly. You may only work 10 to 15 minutes per day, always ending on a good note. Don’t rush it, and always return to basics if your horse appears worried, confused, or gets stuck.

Reward Forward Motion

Hold the halter in front of you and wait for your horse to touch it. Reward the touch or “target” behavior.

If your horse will consistently touch the halter, change your grasp. Hold the halter so that the noseband is round and he has a “hole” where he can put his nose. Now, you won’t mark when he touches the halter, but only when he reaches his nose farther into the hole. Be patient and wait for the horse to reach out and touch it. You may even hold it so that your horse has to move forward to touch it. If this is too much, return to a previous training level.

If your horse gets stuck at this point, change it up. Play “follow the halter” to reinforce his halter-touching behavior around the paddock. Your horse will learn to touch the halter after you have walked a few steps. If your horse is walking with you and allowing you to approach his left side (where you want to be to put on a halter at the end of training), return to the nose-in idea.

Move the halter farther away, and wait for your horse to move forward to touch the halter. Make sure to praise any forward motion toward the halter until your horse consistently targets the halter. Holding the halter out away from you will also help your horse learn that it’s touching the halter, and not seeking the treats from the pouch, that gets the reward.

Open Armed

Once your horse will put his nose into the halter, move on to the next step. Now, you’ll hold the right (long) piece of the rope halter in your right arm and keep the noseband rounded with your left hand. Keep your right elbow up and bent to make a wide open window. You’ll ask your horse to put his nose through the circle created by your arm and the halter.

Reward your horse, at first, for not moving away. Then request more from him. Only reward him when he puts his nose through the hole. Then only reward him when he puts his nose through the hole and down into the noseband.

All In

If your normally hard-to-catch horse is willing to put his nose in and keep it there, he may be ready for you to move the crownpiece back to tie. Proceed slowly; don’t get eager. If your horse pulls away at all, or looks tense, go back to something easier, then proceed on another day. Keep using your marking word, and give treats consistently.

Moving your hand up to move the long halter piece over his head may take time. If your horse accepts the halter, simply take it off and give treats. Make sure your horse knows that putting the halter on doesn’t lead to work. Help your horse feel calm and rewarded.

Then attach the lead rope to the halter. Some horses may notice that something is different and become worried again. Start back at the early stages of halter touching to build confidence again.

Even with the lead rope in place and the halter on, make sure not to put your horse to work right away. Take the halter off and reward your horse.

Continuing the Plan

Practice your new haltering plan daily. Once your horse will allow you to halter him easily, show him that being haltered leads to something good. Halter him and take him to hand graze for a few minutes before turning him loose. Help your horse associate you with not only treat rewards, but with activities he enjoys.

Eventually, you’ll want to get out of this awkward halter-targeting position and hold the halter as you would with any horse. Approach your horse from the side and notice if he tenses. If you see any resistance or he moves away, return to your earlier work and keep working on your side approach over time.

This article about training a hard-to-catch horse appeared in the November/December 2020 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!