We’ve all experienced it: a horse that won’t give to the bit, pulls back when you ask for his head or just completely ignores your rein cues. Horsemen have a term for this syndrome—hard mouth.

The term “hard mouth” conjures up images of a horse with concrete jaws and steel gums, bracing himself against a skinny little bit that has no hope of making an impression. In reality, the syndrome of a hard mouth is less of a physical issue and more of a psychological one. Horses with hard mouths have simply learned to resist the bit.

“A horse’s natural reaction to pressure is to resist,” says Courtney Meitz, a reining and cutting horse trainer at Willow Glen Equestrian Centre in El Cajon, Calif. “A hard mouth usually develops when we fail to teach the horse to give to pressure, and he gets used to pulling against the bit. Many people go to a more severe bit to control the horse, and pretty soon that one is not strong enough, either. A stronger, more severe bit is only a quick fix, with very limited effectiveness because the horse becomes more and more resistant to it. The horse and rider end up stuck in a vicious cycle.”

Poor training and poor riding skills are usually the culprits in the development of a hard mouth. “Overuse of the hands, transferred to the bit, combined with the lack of training in teaching the horse to respond to the rider’s leg and seat, is where most of these problems usually start,” says Laurie Takoff, owner of Laurian Quarter Horses in Kelowna, B.C., Canada, and a member of the American Quarter Horse Association of Professional Horsemen.

Laurie points out that the problem can even develop in well trained horses that are constantly exposed to riders who rely too much on their hands for control, instead of using their legs and seat.

“This is a problem most often seen in beginner or novice riders,” she says. “For novices, using the hands, arms and upper body for control offers a greater feeling of security in controlling and steering the horse.”

Consequences

Not surprisingly, horses that have learned to resist the bit are not easy to ride. Problems such as refusing to stop or slow down, the inability to flex or bend, and a tendency to brace the head and neck against the reins, are all issues with hard-mouthed horses.

“Hard-mouthed horses are protecting themselves from pain caused by extreme bit pressure in their mouths, or the pressure of the hackamore or bosal on the nose and chin,” says Kim Hayes, riding instructor and trainer in both the English and western disciplines, in Arvada, Colo. “These horses develop defense mechanisms to lessen the pain, such as bracing their heads and necks against the reins, and are difficult to slow down or stop. Hard-mouthed horses also stiffen up when you try to bend or flex them, causing flat turns and jolting transitions. Often, the very things that horses do to lessen the pain cause riders to stiffen up more and pull harder on the reins, creating a cycle of pull—brace—pull harder—brace harder—that only ends in frustration for rider and horse.”

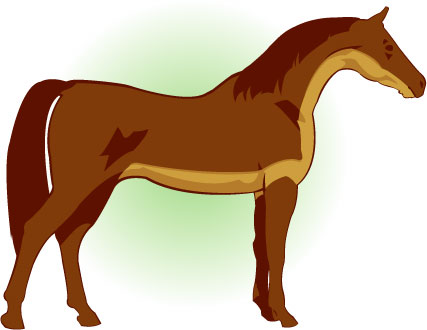

“Hard mouthed horses are commonly known for ‘running through the bit or bridle,’ ” says Laurie Takoff. “This can often develop into the horse becoming very heavy on the forehand and lacking the drive from behind needed to respond properly. I have also seen these horses overflexing at the poll and neck or not flexing enough.”

According to Laurie, overflexing can develop to the point where the horse uses his neck as well as his mouth to pull on the rider’s hands. “When this happens, the rider has a tendency to lean back in the saddle too far in an effort to move the horse’s center of gravity back and gain leverage by pulling back on the reins,” she says. “This can put quite a bit of pressure on the horse’s back and loins, which can develop into chronic pain if not corrected.”

Cures

Hard mouths are not impossible to fix. The key to softening the mouth of a resistant horse is careful retraining. Courtney Meitz starts with bending work.

“The remedy starts by going back to the beginning,” she says. “The first thing I’ll do when I get on a horse with a hard mouth is put him in a snaffle and find out if he knows what the word ‘whoa’ means. If he doesn’t, that’s the first thing he needs to learn.

“I start him off at a walk, then I say ‘whoa.’ If he doesn’t stop, I draw the reins back until he does. As soon as he stops I release him. Then I will walk again and say ‘whoa’ again. If he doesn’t stop, I’ll repeat the above, but this time I’ll ask him to back a few steps. This will explain to him not to push into the bit. Eventually he’ll hear the word ‘whoa’ and know what is coming next, so he figures he may as well stop. When he does it without the rein aid I praise him and let him stand for a while.” However, Courtney also makes sure the horse knows “whoa” on the ground. “If I’ve started the horse, ‘whoa’ in a halter and lead rope is part of leading training. If the horse comes to me with some training already, I’ll go back and make sure he knows ‘whoa’ on the ground.

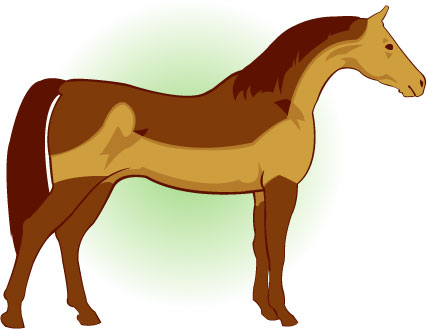

“[Once the horse knows ‘whoa’] I’ll spend as much time as necessary to get him soft at the walk first. I do this byasking him to follow his nose in a circle. I will take [the inside] rein and slowly bring my hand to the outside of my hip and ask for a little bit of bend. Not too much—I want it to be somewhat easy. How much bend is dependent on the individual horse. A horse that is really resistant I may only ask to the point where I see about three-quarters of his eye. I’ll eventually bring his nose around almost to his shoulder, but how long it takes to get to that point depends on the horse. As soon as he gives to the rein pressure, I release and let him walk straight—that’s his reward. I do this until I can take one rein, and, before there’s any contact with the bit, he curves his neck, steps over his inside front and walks softly and relaxed on a small circle. Once I have achieved this, I’ll ask for bend in a larger circle, using my inside leg to push him out a little.”

Courtney follows bending work with reinforcing the “whoa” command. The horse should have a good “whoa” at the walk, jog and lope. She then asks the horse to bend as he’s walking in a straight line, and then eventually adds counter-bending, all the while rewarding the horse for giving to the bit.

“It may take awhile to achieve, but trust has to be earned before I can really ask him to be light in the mouth,” she says. “All of this prepares the horse to bridle up and be collected.”

Laurie Takoff also recommends returning to the basics when retraining a hard-mouthed horse, using bending and flexing to teach him to give to the bit. “Suppling exercises are a super way to start working to lighten up the mouth,” she says. “The rider must remember to always use the leg and seat first, and in some cases, voice commands, prior to the reins.”

Whenever working with a horse with a hard mouth, it’s important to resist the temptation to use a harsher bit. “A more severe bit, or switching to a hackamore or bosal, is never the answer to correcting a horse with a hard mouth, since the underlying issue is the rider,” says Kim Hayes. “If you give a rider with hard hands a more severe bit, you only amplify the problem or cause other issues to develop as the horse tries to protect himself from pain.”

Before a horse can be retrained to respond properly to the bit, the rider must have a good seat and balance. Working on a longe line with an instructor can go a long way to developing a balanced seat for a rider, and thus less reliance on the reins for support.

“Once a rider is balanced and using the seat correctly, it’s time to work on softening the horse’s response to bit pressure,” says Kim. “Start off at a standstill, and pull out gently, not back, on one rein until the horse bends his neck around without pulling or bracing against the hand. Keep the hand pressure gentle but steady, and as soon as the horse gives to the pressure—even the tiniest little bit—reward him by releasing the rein. At first, the horse won’t be able to bend around that much, and it’s very important at this point that the rider stop pulling once the horse starts to give.”

Once the horse is giving easily to the bit at the standstill, the rider should work on gentle flexing from side to side at the walk. Next comes the walk-to-halt transition. “Imagine your shoulder blades are like thumbtacks that will drop down into the horse as you ask for the halt,” says Kim. “The idea is to let your weight sink down into the saddle, without slouching or leaning forward or backward. Bend your knees as you ask for the halt to avoid pushing up from your stirrups. You should feel your seat bones ‘plug’ into the saddle like you would push an electrical plug into an outlet. The upper thigh should squeeze gently to slow down the motion in the horse’s back. Practice this walk-halt transition using the seat aids first, reinforcing lightly with the reins after the seat aids are given. Don’t worry if it takes a long time for the horse to stop at first—he needs to learn the new aids too. As horse and rider start gaining confidence in each other, try downward transitions from faster gaits.”

Realizing the causes of a hard mouth is the first step to correcting this training problem. A professional trainer can help the horse learn to give to the bit, and good instruction can teach a rider to have soft hands. With patience, persistence and practice, the hard-mouthed horse truly can develop a softer outlook on life and become a more enjoyable ride.

Other Trouble Spots

Most horses develop hard mouths as a result of poor riding and training, but on occasion physical problems can be the cause of poor response to the bit.

“Back pain should be considered in finding and curing the problem in the hard-mouthed horse,” says Laurie Takoff. “A horse with back pain might learn to pull on the bit in an effort to lift the rider’s weight off his back, thus reliving his pain.”

Laurie also suggests looking over the horse’s tack for potential problems. “Make sure the saddle and girth fit properly, and that the saddle pad is adequate,” she says. “Also, look over the bridle and bit to ensure they fit properly and are not pinching.”

Dental care is also crucial in maintaining a healthy mouth that will readily accept the bit. “Good regular dental attention is important for all horses,” says Laurie. “It never ceases to surprise me how much a comprehensive dental treatment can help.”

Laurie also believes a bit seat can help—which involves rounding and smoothing the second premolars in your horse’s mouth. Ask your veterinarian if this is recommended for your particular situation.

This article originally appeared in the November 2004 issue of Horse Illustrated. Click here to subscribe.

A freelance equine writer, Audrey Pavia is a former editor of Horse Illustrated and author of “Horses for Dummies.” She has trained in western, hunt seat and dressage, and competes in NATRC-sponsored competitive trail riding. Audrey resides in Norco, California, with her foundation-bred Appaloosa gelding, Confetti’s Valentine, and her two cats.

Nothing can be more satisfying to us vets than a really good hoof abscess. Right from start to finish, they can make our day. It starts with the call, pretty much always the same, “Horse was fine yesterday; very lame today,” and ends with the owner overjoyed that the diagnosis is merely an abscess. Let’s not forget the in-between stuff, such as the really great moment when the vet’s hoof knife hits the spot, making blackish gray stuff pour out. For those who have never experienced a hoof abscess, the moment of relief is, unbelievably, when the pus pours.

Nothing can be more satisfying to us vets than a really good hoof abscess. Right from start to finish, they can make our day. It starts with the call, pretty much always the same, “Horse was fine yesterday; very lame today,” and ends with the owner overjoyed that the diagnosis is merely an abscess. Let’s not forget the in-between stuff, such as the really great moment when the vet’s hoof knife hits the spot, making blackish gray stuff pour out. For those who have never experienced a hoof abscess, the moment of relief is, unbelievably, when the pus pours.

The Basics

The Basics