In a search for their roots, South Korean equestrians are reviving the 230-year-old sport of horseback archery.

Park Sung Min clicks her tongue and motivates her horse to run even faster. He breaks into a fast gallop, and Park Sung Min rises in the saddle, raises her bow, and sends an arrow hurtling toward the shooting target a few meters ahead of her.She misses the target, but it doesn’t stop the young woman. Park Sung Min barely sits in the saddle before she rises again. A few meters further on, the next target awaits. Park aims, and this time she hits it.

Background of Horseback Archery

Although it may seem like it, I’m not observing the filming of a Western, and Park Sung Min is neither an actor nor an American.

Instead, I am standing in South Korea, in the small town Hwaseong in Gyeonggi Province south of Seoul, where I watch the last traditional equestrian martial arts competition of the season.

It has only been 35 years since the restoration of South Korea’s traditional equestrian martial arts began. Although the sport is more than 230 years old, it disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century.

Today, the equestrians on the farm in Hwaseong are fighting to revive and reinvent the sport. That means live performances, help from Gyeonggi Province’s capital city Suwon, and a lot of hard work.

How do you revive a sport if you only have one book from 1790 as your guide? And why have a couple of equestrians and martial artists spent most of their lives rediscovering and promoting South Korea’s cultural heritage?

I went to Hwaseong to find out.

Traditional Attire

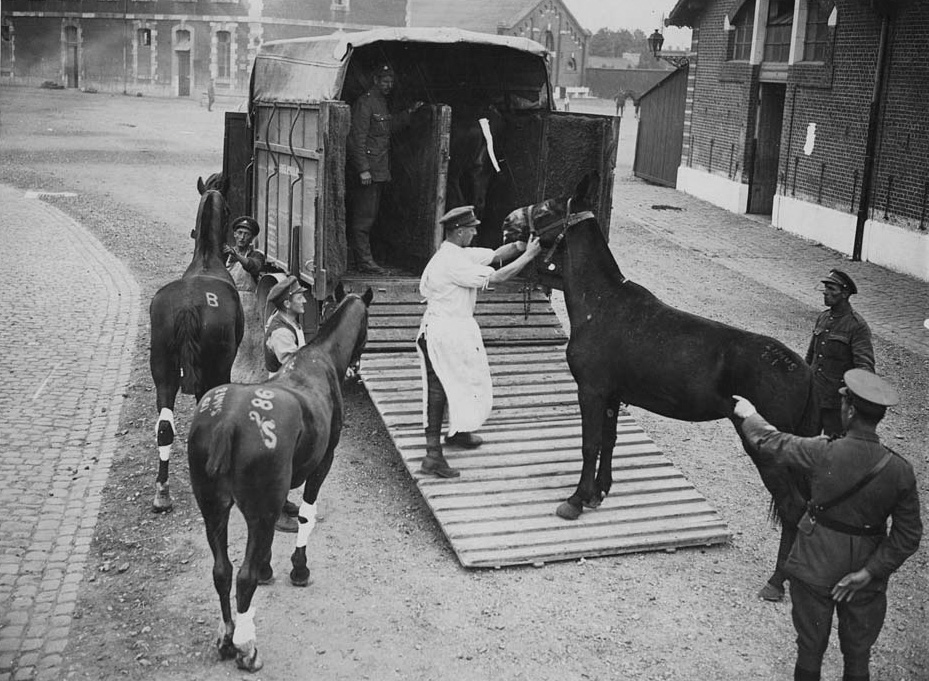

The farm is small and consists of a stable, a paddock, and two riding arenas. The horses look at me just as curiously as the competition’s riders and spectators, who normally don’t see foreigners in this part of the country.

The day starts at 12 o’clock with a competition in South Korea’s traditional martial arts kisa—horseback archery.

Some of the participants are dressed in traditional Korean clothing which, unlike breeches, are loose, white trousers with wide legs. Park Min Song is also wearing a hanbok top, similar to South Korea’s traditional clothing. The hanbok shirt is sky blue and tied together over the chest with a small, red ribbon.

Just before getting on the horse, Park Min Song ties on a pair of silver bracers to protect her forearms from whiplash from the bowstring.

How Horseback Archery Works

The competition is simple: Gallop your mount and fire a few arrows at some shooting targets. The points are awarded according to how quickly and accurately the equestrian shoots.

The equestrians use different strategies. For some, it’s about making the horse run as fast as possible. For others, like Park Min Song, it’s the precision of the shots that matter.

After just over an hour, Park Min Song wins the competition.

The young woman has been riding for nine years, and for seven of those, she has been training in Korean equestrian martial arts. Today, she is part of a performance group established by Suwon city that demonstrates equestrian martial arts during Korean national holidays and events.

“I always liked working with my body, and I did martial arts before finding out about this horse sport,” says Park Min Song. “It’s really interesting, because it’s a mix of learning about the history of my home country and exercising.”

A Family Activity

It’s primarily families who have turned up for today’s competition. Many of those I speak to say that they are fascinated by the sport, mainly because it’s fun and challenging for children and adults alike. They also enjoy the connection it has to their history and culture.

After the horseback competition comes the highlight of the day, which is an archery competition for elementary school children.

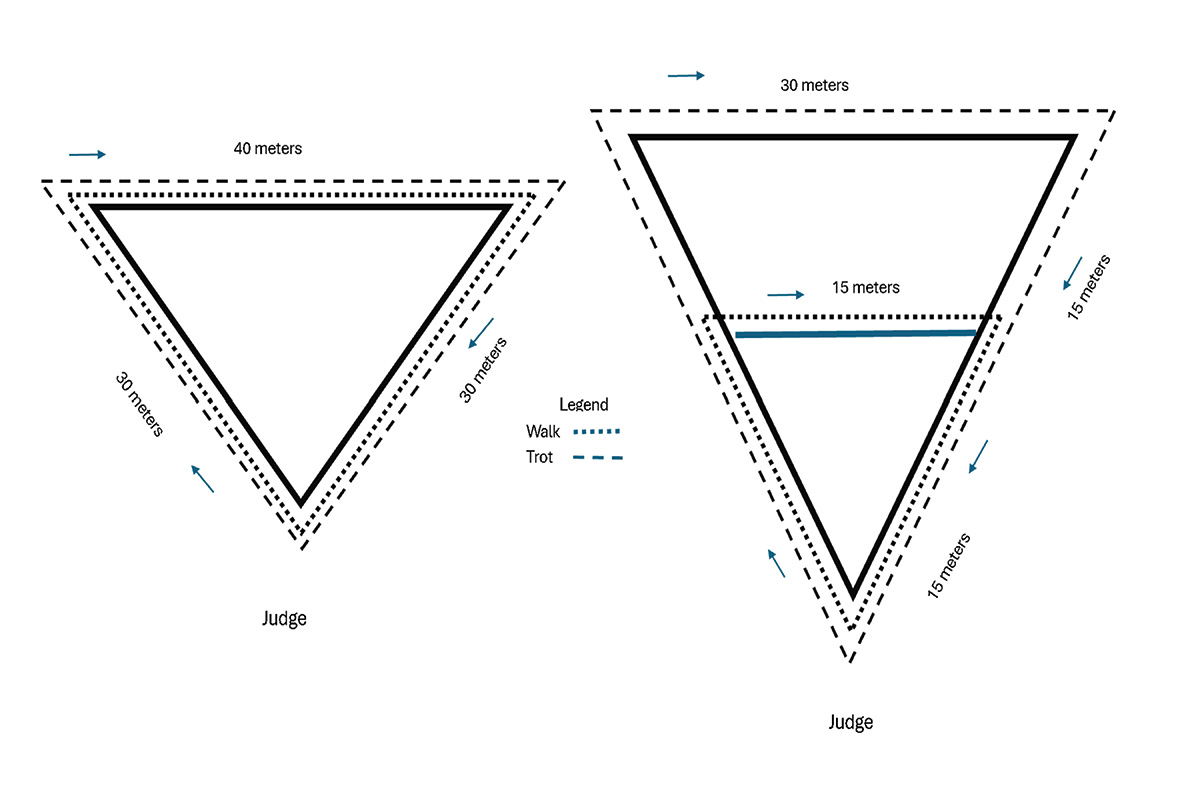

The spectators move from the riding arenas to a shooting range, where a number of children are already lined up and ready to compete in 15-meter archery. The winner is 12-year-old Han Tae Hyung, who has been practicing archery and horseback archery on the farm for two years.

His mother learned about the sport through some friends, and since Han Tae Hyung is fond of horses, he decided to start practicing.

“I love to ride, and all the horses have become my friends,” he says.

For the traditional equestrian martial arts academy, which is organizing today’s competition, it’s essential to get young people interested in Korean cultural heritage, says Kim Kwang Sik.

Equestrian martial arts remain relatively unknown in South Korea, and Kim is struggling to raise awareness about the sport. Because for Kim Kwang Sik, this is much more than a sport.

The Only Book Left

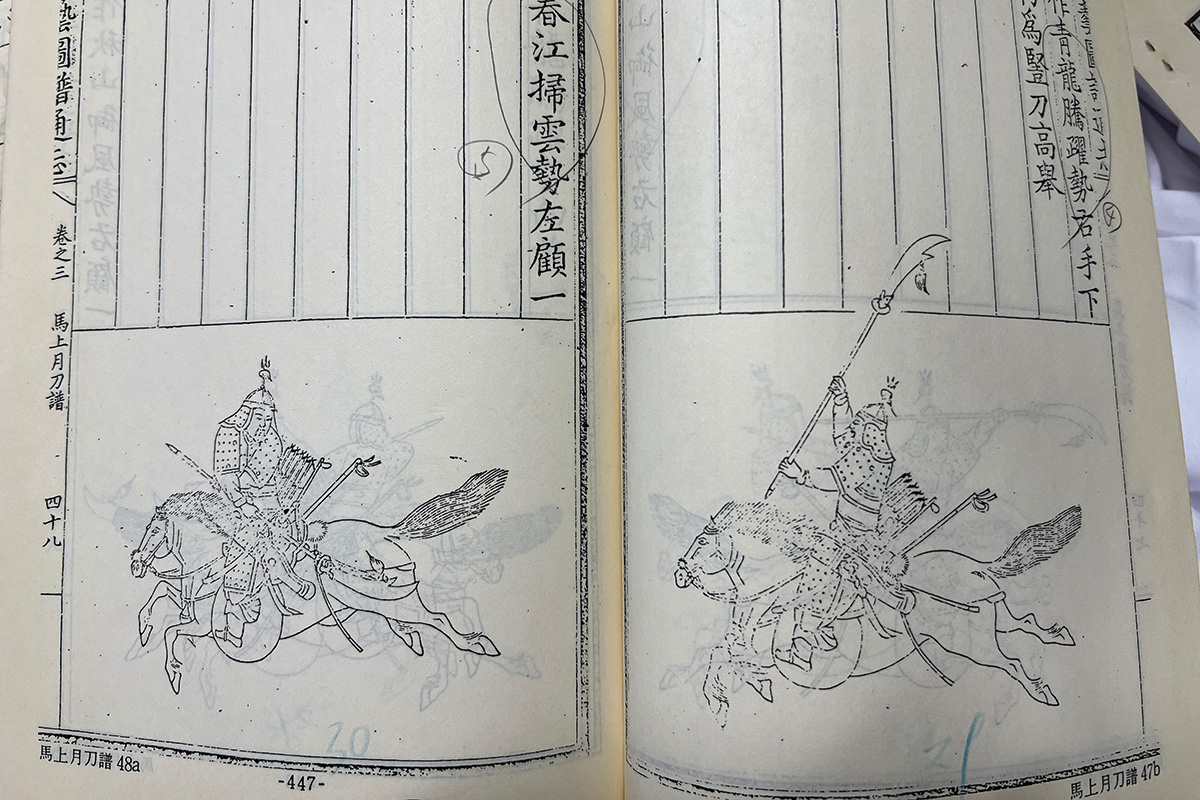

Kim Kwang Sik has always been interested in Korean culture and heritage, but it was when he got his hands on a book from 1790 that he found his life’s calling. The book is called Muyedobotongji, and was written by a military officer, philosopher and martial artist by order of King Jeongjo, Korea’s 6th king.

The book is a basic guidebook for Korean soldiers, and consists of 24 martial arts techniques, six of which are performed on horseback. The book is essential for Korean equestrian martial artists, as all other writings about Korea’s traditional horse martial arts were lost during Japan’s occupation of the Korean peninsula from 1910-1945, when a lot of traditional Korean culture was forcibly destroyed.

Only Muyedobotongji remains, and it’s the only thing Kim Kwang Sik has used to learn and eventually revive the old sport.

“I had a sense of duty to preserve Korean culture,” he says. “I’ve been doing it for more than 30 years, and now people who are interested in Korean history and traditions come here to learn about it.”

Bringing the Sport to Life

When he decided to work on bringing back the old sport, Kim Kwang Sik was largely on his own. He had to figure out for himself how to train the horses to be calm around swinging swords and bows and arrows. The martial arts book (whose copy can be found in a small office next to the stable) left a lot to the imagination when it came to the execution of several of the techniques.

“One of the things that makes this sport fun is that it’s a way of half reading a book and half figuring it out yourself,” laughs rider Bae Kuk Jin, who has practiced traditional equestrian martial arts since 2008, and who also participates in today’s competition.

But Kim Kwang Sik’s hardest task has not been training horses nor interpreting writings and illustrations from 1790. It has been getting funding and support from the Korean government.

“There is no national support to revive the equestrian martial arts,” says Kim Kwang Sik. Only Suwon city has supported the sport and created an equestrian martial arts team.

“Suwon city is the first city that is trying to preserve this,” he continues. “They have asked the government to help because it’s important to preserve.”

However, support might be on its way. In 2017, Kim Kwang Sik managed to get the martial arts book on UNESCO’s World Cultural Heritage list, and that’s a start.

When I ask Kim Kwang Sik why it means so much to him to preserve and revive traditional equestrian martial arts, he has only one answer.

“I’m not sure if I believe in Buddhism or not, but I think in my previous life, I was a soldier,” he says with a smile.

This article about Korean horseback archery appeared in the June 2024 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!